Santa Cruz County is home to Tumacacori National Historical Park, nestled in the upper Santa Cruz River Valley in southern Arizona. The park spans 360 acres over three sections, with remnants of three separate Spanish mission towns, two of which are recognized by the United States government as National Historic Landmarks, scattered within the park’s boundaries.

Go back in time to the 19th century and see this Franciscan mission that American Indian and Spanish workers constructed under the supervision of a master mason. Even though construction on the church at Tumacacori was never finished, the incomplete structure is still a prominent feature of this National Heritage Monument.

Keep reading if you want to learn more about Tumacacori National Historical Park.

History of Tumacacori National Historical Park

Tumacacori’s story is about an intricate network of cultures and periods spanning many continents. There are many stories, from hardships to triumphs, from hard work to relaxation. The events depicted here occurred in a historical setting and were experienced by actual individuals. Historians with a thirst for knowledge are still unearthing some of them.

The former Tumacacori mission is one of the earliest national park sites in the United States, designated as a national monument in 1908. Nevertheless, the site would take another 80 years to be recognized as a National Historical Park.

The O’odham five sister nations, the Tohono, the Pima, the Yaki, the Apache, and the Mexicans, all called this area home long before the arrival of missionaries. In the 1600s, when Spanish missionaries came, they renamed the area Pimería Alta, which means “place of the higher Pimas,” after one of the Spanish names for the O’odham.

Jesuit priest Father Francisco Kino came to the Pimería Alta in January 1691 and built the Tumacacori Mission, making it the earliest mission in Arizona. The mission was officially renamed San José de Tumacacori after relocating to its present location and further movements after the Pima revolt of 1751.

When the Franciscans took over management of the village in 1800, they began building the church that still stands on the grounds. They modeled it after the San Xavier del Bac Mission in Tucson. Construction didn’t wrap up until 1823 due to several setbacks. Around five years later, when Spain was finally ousted from Mexico, the last resident priest in Tumacacori also left.

The old church building was already in a bad state by the time it was designated a national monument. The yearly rains had eroded portions of the original masonry and caused the roof to collapse completely. The remains are still there because of conservation efforts, and in the late 1930s, a visitor center was built to hold exhibitions utilizing materials salvaged from the original mission structures.

The abandoned remains of three of these historic Spanish colonial missions may be seen at Tumacacori National Historical Park in Santa Cruz River Valley of southern Arizona. San Jose de Tumacacori and Los Santos Angeles de Guevavi that were established in 1691, are the two oldest missions in Arizona, and San Cayetano de Calabazas, built in 1756.

Top Things to See and Do at Tumacacori National Historical Park

The Franciscan-era church San José de Tumacacori is the most well-known structure in the park. However, there is also a museum, a Melhok ki, which is a replica of an O’odham home from the period, and the remnants of the mission convent and cemetery.

Missions Los Santos Angeles de Guevavi and San Cayetano de Calabazas, two further outlying missions preserved by the park, are only accessible through pre-arranged trips from January to April.

Only some people know Tumacacori, although Arizona is home to national parks such as the Grand Canyon, Saguaro, and Petrified Forest. Nestled in the desert of Southern Arizona, the lesser-known Tumacacori National Historical Park preserves the remnants of a Spanish mission established in the 1820s. The park, though, stands for much more than that.

The mission grounds at a cultural crossroads protect the histories and tales of the O’odham, Yaqui, and Apache people and those of European missionaries, settlers, and soldiers. The mission’s grounds are a testament to their turbulent and ultimately fruitful history of working with and against one another.

When visiting the Heritage Park, you may participate in the following activities:

Visit the Church

Local settlers demolished the roof and used the wood for their own purposes when the church was abandoned in 1848. The paint faded, and the plaster peeled off the walls in most places due to exposure to the hot desert heat, giving the inside a considerably older appearance.

People either stood or kneeled during mass in the church’s vast hall. You can still see bits of old paint on the walls as you go down the main hallway to the sanctuary with the dome ceiling.

Go up to the bell tower if you don’t mind the steps. You may get there by entering the baptistry to the right of the main door. The bell tower is located on the third floor, up a flight of stairs from the choir loft.

Discover the Mission Grounds

The sacristy, where the priest would prepare for the service, leads to the inner court, where you’ll find a storehouse and the cemetery behind the church. You’ll discover the Convento Complex near the church on the right.

Contrary to what the name would imply, it was not a convent but rather a collection of structures for communal use. Many rooms surround a central courtyard. They served as the priests’ homes, a kitchen, an ironworker’s shop, a carpentry shop, and other functions.

Appreciate the Diversity of Cultures Represented in Tumacacori

The park also hosts unique activities that honor the traditions of the local desert population.

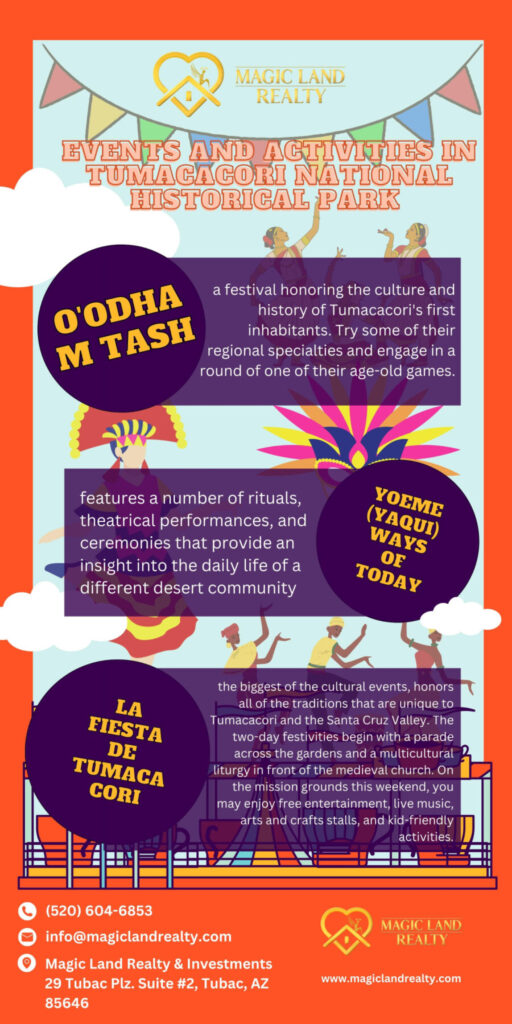

- The O’odham Tash is a festival honoring the culture and history of Tumacacori’s first inhabitants. Try some of their regional specialties and engage in a round of one of their age-old games.

- The Yoeme (Yaqui) Ways of Today features several rituals, theatrical performances, and ceremonies that provide an insight into the daily life of a different desert community.

- La Fiesta de Tumacacori, the biggest of the cultural events, honors all of the traditions unique to Tumacacori and the Santa Cruz Valley. The two-day festivities begin with a parade across the gardens and a multicultural liturgy in front of the medieval church. On the mission grounds this weekend, you may enjoy free entertainment, live music, arts and crafts stalls, and kid-friendly activities.

Wrap Up

The abundance of culture and history of Tumacacori National Historical Park makes it an absolute must-see. Families and people searching for a location to spend their time on the weekends would find this historical site excellent, particularly with their children’s education.

If you have any questions about Tumacacori National Historical Park or any other Arizona local guides, please do not hesitate to call me at (520) 604-6853 or email me at info@magiclandrealty.com.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are some of the park's most popular attractions?

The 1848 Franciscan-era church at Tumacacori National Historical Park is a significant draw for visitors. Even though ancient, people are often taken aback by the church’s beauty and history.

What is your favorite thing to do at Tumacacori National Historical Park?

Tumacacori National Historical Park has a lot to offer, but one of my favorite things to do there is to learn about the park’s rich cultural past.

What are some of the unique historical features of Tumacacori National Historical Park?

Tumacacori National Heritage is notable for its many historic structures, including a museum, a Melhok ki (a reproduction of a traditional O’odham home), and the remnants of a mission convent and cemetery.

Why do you think it is essential for people to visit heritage sites like Tumacacori National Historical Park?

Heritage sites, such as Tumacacori National Historical Park, are important because they represent a magnificent achievement of humanity and provide proof of our intellectual history on Earth; they are also a means for us to honor the people of the past who made sacrifices so that our generation may succeed.

How does Tumacacori National Historical Park reflect the cultural and historical heritage of the United States?

Tumacacori National Heritage is dedicated to preserving the past and sharing the tales of the Spanish missions that profoundly impacted the Pimería Álta’s American Indian populations and the region’s ongoing culture.

Historic preservation is an integral component of the United States’ rich culture because the structures, ruins, and artifacts it protects serve as reminders of humanity’s progress and evolution.